The Evolution of Heterogeneous Processing

And Why It's a Headache for Kernel Developers

In the early days of computing, machines had a single logical core. So how did they manage to juggle multiple tasks? The answer came from Bell Labs, where AT&T engineers created Unix in the 1970s. Rather than letting one job monopolize system resources until completion, Unix introduced preemptive scheduling—the operating system could interrupt tasks and switch between them. (Interestingly, Windows 9x and Mac OS 9 took a different approach, relying on cooperative multitasking where programs had to voluntarily yield control.)

Even with clever scheduling, the limitations of a single core became increasingly obvious. Processor architects responded with symmetric multiprocessing (SMP), allowing multiple jobs to run concurrently across several processors while reducing the need for constant task switching.

Enter Heterogeneous Multiprocessing

SMP boosted performance, but it came with significant energy costs. Embedded and mobile systems needed both high performance and efficient power consumption—a tricky balance. This led microarchitects to develop heterogeneous processors for heterogeneous multiprocessing (HMP). The most successful early implementation was ARM’s big.LITTLE architecture (later succeeded by DynamIQ), which now powers countless embedded and mobile devices.

HMP was revolutionary for consumers and many engineers. For kernel developers, however, it created a new set of challenges.

The Scheduler Problem

To fully utilize heterogeneous processors, kernel engineers had to modify their schedulers to exploit the hardware’s unique characteristics while keeping the code machine-agnostic. Since heterogeneous processors come in wildly different configurations, writing a scheduler that benefits all HMP systems without introducing regressions is genuinely difficult.

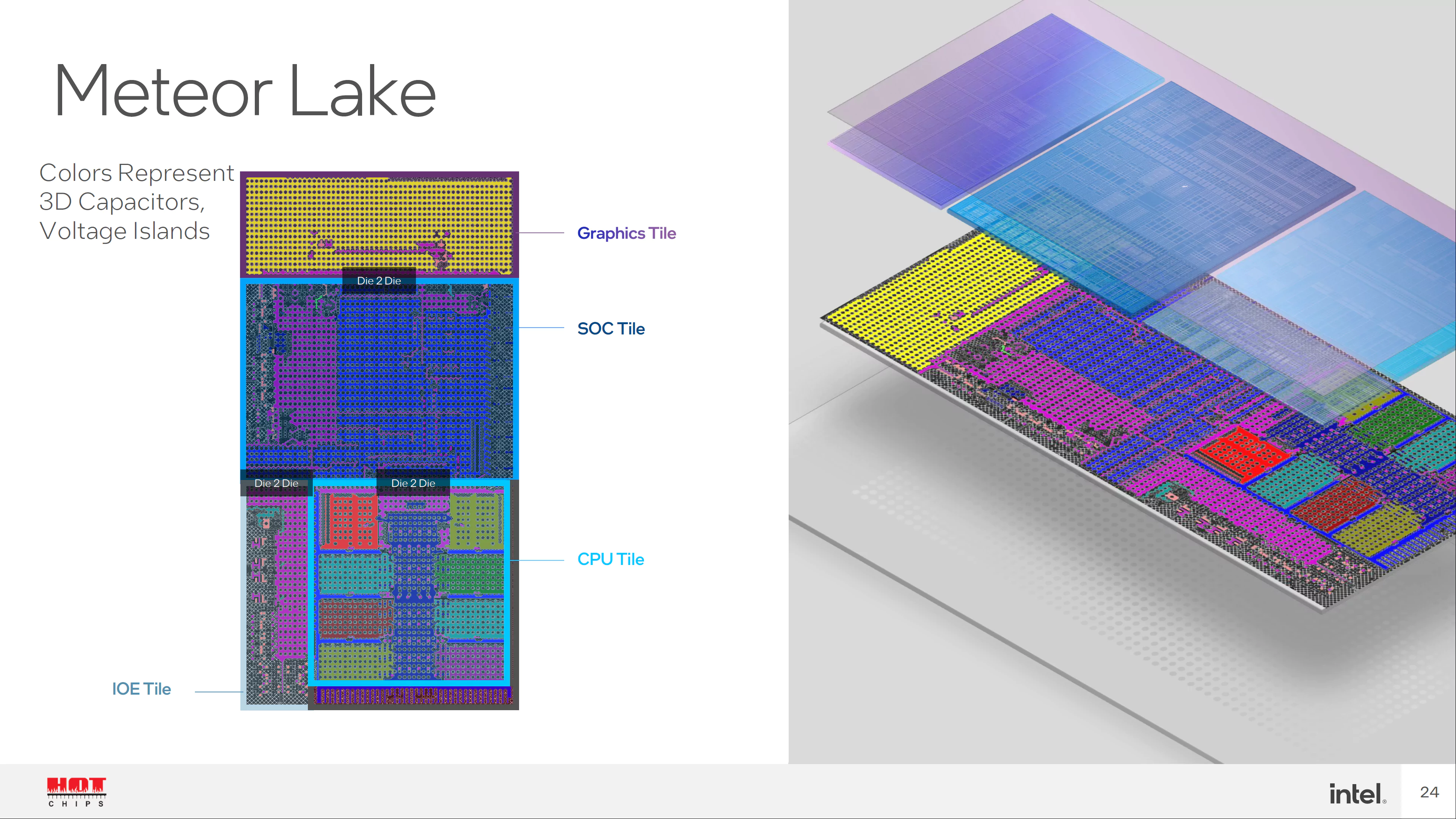

Consider Intel's recent architectures as an example. Meteor Lake laptop processors feature Performance cores, Efficiency cores, and Low-Power Efficiency cores. Each P-core has its own L2 cache, while all E-cores share one L2 cache. The LP-E cores share yet another L2 cache and lack access to the L3 cache entirely—they sit on a separate SOC tile, while only cores on the compute tile can access shared L3.

Then came Panther Lake, which changed the arrangement again. Now LP-E cores reside on the compute tile, giving them access to the shared L3 cache alongside the other cores.

Capacity-Aware Scheduling

As you can see, naively assigning tasks based solely on core type is a losing strategy. Schedulers need actual data about each core’s processing capacity to distribute work efficiently. On systems using device trees, this information comes from the cpu-capacity field, which typically represents Dhrystone benchmark scores divided by the CPU frequency at which the benchmark ran (DMIPS/MHz). The kernel normalizes these values to a 0–1024 range for machine-agnostic scheduling. The Linux documentation on cpu-capacity and capacity-aware scheduling covers this in detail.

One of my current projects in the FreeBSD Project involves bringing HMP scheduling capabilities to the operating system. I’ve started a mailing list thread for discussion and submitted an initial patch.

When Things Get Weird

The challenges multiply with unconventional configurations—like systems mixing Arm Cortex-A and Cortex-M cores. Cortex-M processors lack proper MMUs for general-purpose operating systems, and combining the two requires special handling since this isn’t a standard big.LITTLE setup. Typically, a dedicated device driver distributes tasks to Cortex-M cores rather than integrating them into the main scheduler.

Even worse are processors that look like valid heterogeneous designs but are fundamentally broken. Mixing cores with different ISA versions or cache line sizes causes real problems. Instructions like DC ZVA depend on cache line size and will behave differently when a task migrates between cores with mismatched configurations. Arm explicitly prohibits this, but some architects apparently skip the documentation and build whatever they want.

The Bottom Line

To be clear: heterogeneous processors matter, and kernel developers should absolutely work to support them. But when hardware designers arrive with nonsensical configurations and expect kernel developers to accommodate their special snowflake device, there’s only so much we can do. At that point, the options are straightforward: redesign the hardware or write your own device driver.